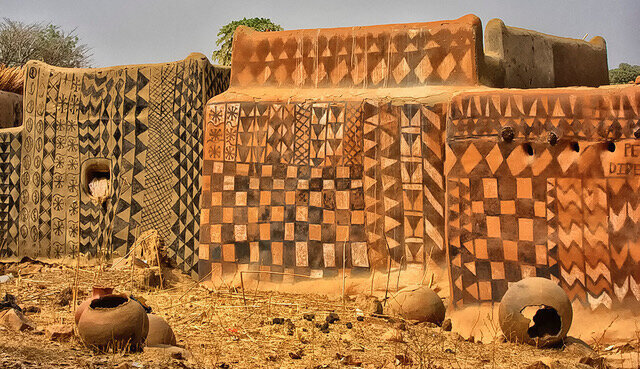

West African Ghanaian Adinkra Cloth

Journey with a quest: Ntonso village to meet master artisans of Adinkra cloth

After the Akwaesidea in Kumasi, I wanted to meet the artisans who created the exquisite Adinkra cloth for the dead. At his family compound in Ntonso, not far from Kumasi, Ghana, Peter Boakye and three generations of this family work like a well-oiled machine producing sumptuous adinkra cloth for people to wear at funerals and other ceremonial occasions. The cloth is made from white cotton strips that have been sewn together and decorated; motifs can be woven, embroidered, appliquéd, screened, or hand-stamped onto adinka cloth. In the past, cotton fabric was hand-woven, but today machine-made cloth is preferred.

The Boakye family compound is divided into their residence and their workshop, where Peter Boakye and his brothers prepare natural dyes by soaking, pulverizing, and boiling bark and roots from the badie tree (Bridelia ferruginea) for making the designs and barks and roots from the kuntunkuni (Bombax brevicuspe) tree for a russet brown, if they desire a different background color instead of a white cloth. Whenever I bring visitors to the workshop, Peter, the third-generation Boakye, is usually kneeling over a long wooden plank covered with a multi-paneled cotton cloth and hand-stamping motifs on the cloth using a stamp made from a gourd. (See banner photo at the top of the page.)

Filtering the badi bark dyestuff to extract the dye, which is then boiled.

How adinkra cloth is made

Making adinkra cloth is time-consuming; it takes many months to collect the bark and roots from the kuntunkuni and badie trees in the forest, and a few days or more to extract the dark brown and russet brown colors from the bark and roots, before hand-stamping the designs onto the fabric. Some cloths are huge, up to 12 feet long and 7 feet wide, and require more than one person to make the patterns.

Calabash stamps soaked in Badie dye for stamping adinkra cloth

The actual making of the design is the function of a hand-made stamp, a technique which Peter’s family is known for. The stamps are made from a small piece of a thin calabash gourd that has been seasoned with shea butter from the kerite tree. After this piece of gourd has been cut out and scraped off, the symbol or image is carved in relief with a small knife on the bottom side of the gourd. Then raffia palm or bamboo sticks are hammered into the back of the stamp. A cloth or wrap is tied to these to make a handle.

Once the print dye has been prepared, Peter takes a hand-woven and dyed cloth (or factory dyed which is cheaper) and stretches it flat on a long padded board for hand-stamping. He then draws squares onto the cloth using a pronged comb and stamps a motif inside each square, but sometimes they stamp the design without using squares. The symbols have meanings and can be used on metal, wood, calabash bowls, and clay. (You can refer to our page on Symbols to see some of the more popular ones stamped on calabashes.) Peter must stamp the cloth in a fast rolling manner, so it goes on evenly. He uses the stamps requested by the family for the deceased, or if the family requests, he can select the specific stamps for the person.

Carved calabash stamps with various symbols

The artisan draws squares on the cloth with a pronged comb

Badie bark that has been pounded before boiled.

Peter making black dye from roots of Kuntunkuni trees.

Calabash stamp on adinkra cloth