Bani Ferry

West African Mud Cloth

Journey with a quest: Djenne, Mali to meet a famous mud cloth artisan

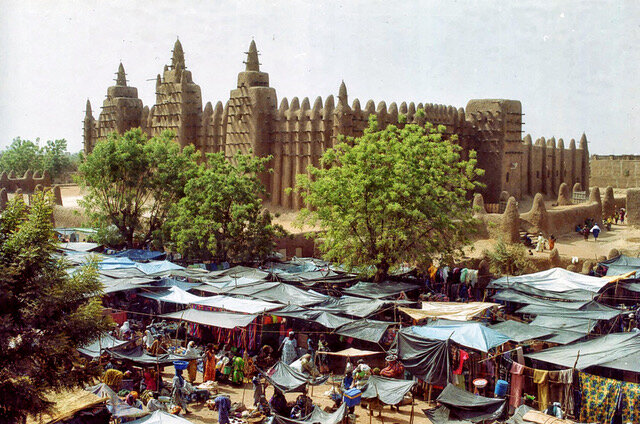

“Ferry boat is not operating,” shouted one of the older boys standing by the river’s edge. Adama, my Malian driver, immediately put our four-wheel drive into low gear and after beckoning for our “river guides,” he slowly eased our land cruiser into the Bani River, a tributary of the Niger River. Adama assuaged my fears. “Don’t worry, the river is low, and we have the boys to help us, Inshallah.” The young guides, no older than 12 years, waded waist deep in the river ahead of our vehicle, testing the water’s depth, watching for deep depressions that could swallow up our car. As Adama assured me, we crossed safely, the boys were handsomely rewarded with a cadeaux (tip), and Abdoulaye, my guide, and I headed for Djenne, Mali, an ancient trading city celebrated for its Sudanic-style architecture, the renowned Djenne market, and Grande Mosque, the largest religious mud structure in the world.

Djenne mud mosque

Bogolan artist: Pama SInatoa

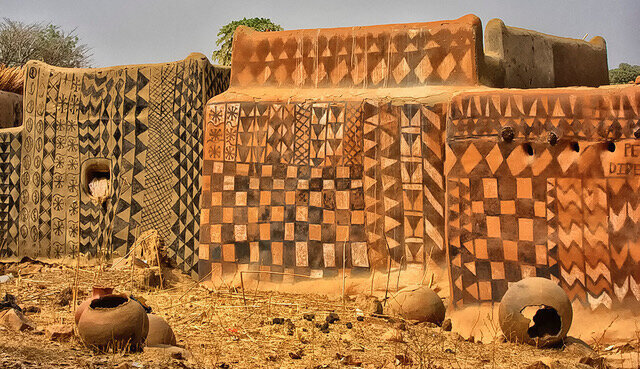

The historic sites brought me to Djenne, but I also wanted to meet a famous bogolan artist, Pama Sinatoa, who makes mud cloth known as bogolanfini in Mali that reflects the history of her Bambara tribe, powerful warriors in the 18th century. Prior to 1980 the Bambara women would pass down the secrets of making bogolanfini cloth to their daughters, following the techniques and designs conveyed through oral history from their ancestors. (Jenny Balfour-Paul, Muddy River Blues.) After Independence in 1960 mud cloth became mass-produced, but here in Djenne, Sinatoa is keeping the art alive using traditional methods she learned as a child.

Sinatoa, Bogolan mud cloth artist

In the Bambara language bogo means earth, lan means with, and fini is cloth. Some cloth had protective powers. Hunters would wear rust-colored tunics of mud cloth adorned with talismans for protection. The cloth would also be worn to mark milestones in a person’s life from birth to death, and each carried a unique symbology.

Talismanic mudcloth tunic (Museum of Black Civilizations, Senegal)

Walking through the meandering mud-walled streets of old Djenne, past the Koranic schools where children recited verses, we came to Sinatoa’s home, not far from the Djenne grand mosque. As we climbed up the steps of her multistory home, I gazed down on the courtyard below and saw large cotton sheets in pale yellow laid out in neat rows. I later learned male weavers produced narrow cotton strips that were then sewn together to form large rectangular sheets. Nearing the top of the building, we entered a large room where Sinatoa sat on a long cushioned bench stacked with finished mud cloth. Wearing a loose pink boubou with crocheted cuffs and bodice, Sinatoa discussed how she creates her unique pieces, which reflect scenes of everyday life in Mali.

Cotton strip weaver using portable loom. Narrow cotton strips are sewn together to form rectangular sheets used for mudcloth among other things. Read more about cotton strip weaving here